Shabtis of ancient egypt

The shabtis of ancient Egypt are favorite pieces of many a museum visitor. To someone who does not know much about ancient times they may look like little dolls, even if their stern appearance does give a hint they had some sort of religious function. Most of them are mummiform, that is they are made to look so that they are wrapped in mummy bandages that only show their head and hands. Some of the shabtis were actually wrapped in linen shrouds as well.

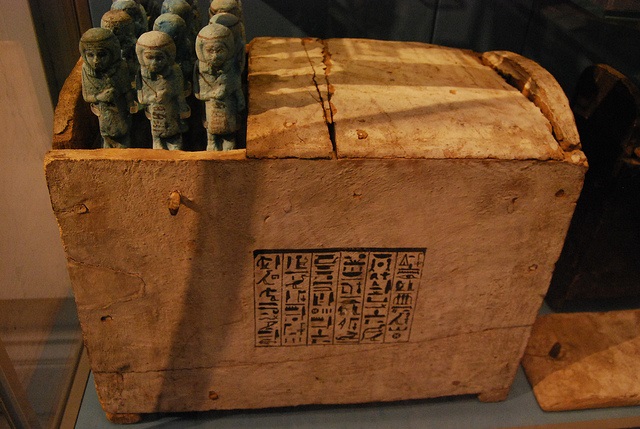

Late Period shabtis from the Ashmolean Museum. Copyright of photo Heidi Kontkanen.

The shabti is linked to the cult of Osiris, the god king of the realm of death. They make their first appearance during the Old Kingdom. First a few shabtis in the tombs of the nobles, and then, as time progressed, their amount increased and even the lower levels of society got their own shabtis. Eventually a person could have hundreds of shabtis – one for each day of the year, and their overseers. All in all this meant 401 shabtis as there was one overseers for ten shabtis.

Overseers? Why would funerary statuettes need overseers?

Shabtis and a shabti box. From the family grave of the royal craftsman Sennedjem at Deir el-Medina. New Kingdom, 19th dynasty.Λ45-46, Λ51-52, (shabti box) Ξ87.Egyptian Collection, Athens Museum. Photo copyright Heidi Kontkanen

Their name reveals their function. The name for them was shabti or ushabti, which means “to answer”. The Egyptians believed that the tomb owner would be called to work in the afterlife, because they believed that the life in the hereafter resembled the world of the living. Therefore all sorts of agricultural work was required. The Egyptians much preferred the idea of resting and having a good life in death after a hard physical life, and wanted to have servants to do any physical labor required.

At the very early Dynastic age the kings took their servants with them – literally. They had the servants killed and buried in subsidiary burials with the king.

Soon enough they realized this was unnecessary waste of experienced officials and servants, and so they invented the shabti – they believed that through magic these little statuettes would be made alive and when the owner of the tomb was called to work, it was the shabti who would answer “Here I am!” and go to work instead of the deceased. They also ran the household for the deceased, and prepared food and drink for them. The first shabti spells, which were to bring the shabtis of ancient Egypt magically alive, are from the 12th Dynasty.

Shabti of Ramses IV. 20th dynasty. N 438 Louvre Museum

So, there were two kinds of shabtis of ancient Egypt: workers and overseers. The workers carried tools – hoes, sacks with seeds for planting. They did all the manual work. The overseers (“reis”) were finely dressed in tunics, kilts, and a triangular apron. And as was proper for an overseer of ancient times, they carried whips in one hand, and their other hand was at their side.

The shabtis could have the facial features of the deceased – a good example of this are the shabtis of Tutankhamun.

The ancient Egyptian shabtis were made of many materials: stone, wood, faience and pottery. The deep turquoise colored faience being the most common. Royal shabtis could be of limestone, sandstone, granite, quartzite, calcite, ivory, bronze and precious metals, serpentine and black limestone. Private shabtis were often made of wood.

Shabtis were often placed in special boxes, and not scattered around the tomb. Sometimes they were put in sarcophagi of their own.

Shabtis were put in tombs from Middle Kingdom onward, up to the Ptolemaic period. So many of them have survived that museums around the world exhibit significant collections of them. And as they have their owners' names written on them, in a way they still do what every ancient Egyptian wanted in keeping their deceased owner's name alive. They believed that as long as a dead person's name survived for posterity, they survived in the afterlife.

Shabtis in a wooden shabti box of Ankhefenkhons. 22nd Dynasty. EA 43436. British Museum. Photo copyright Heidi Kontkanen.

recommended reading about shabtis of ancient egypt

Shabtis – a Private View: Ancient Egyptian Funerary Statuettes in European Private Collections by Glenn Janes (Cybèle, 2002)

The Shabti Collections: 5: A selection from the Manchester Museum by Glenn Janes (Olicar House Publications, 2013)

The Shabti Collections by Glenn Janes: West Park Museum, Macclesfield (Olicar House Publications, 2010)

The Shabti Collections 2: The Warrington Museum and Art Gallery by Glenn Janes (Olicar House Publications, 2011

The Shabti Collections: Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service by Glenn Janes (Olicar House Publications, 2011)

Back to ancient Egyptian mummies and burial

Go to Mummific's version of the shabtis of ancient Egypt

I wish to thank Heidi Kontkanen for the permission to use her wonderful photographs of shabtis as illustrations for this articel.

Tutankhamun: In My Own Hieroglyphs

|

Tutankhamun tells about his life - and death. The book that was chosen to travel the world with Tutankhamun's treasures world tour of 10 cities from 2018 onwards. |

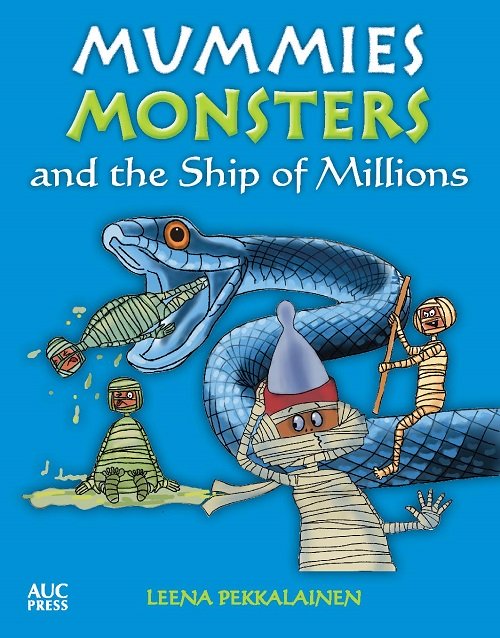

Mummies, Monsters and the Ship of Millions

Mr Mummific's hilarious journey through the 12 caverns of Duat to reach the Field of Reeds.

nephilim quest

Story of the search for one of the oldest legends of humankind, intertwining modern times and ancient Egypt.

preview Nephlim Quest 1: Shaowhunter online.

preview Nephlim Quest 2: MOON DAUGHTER online.

preview Nephilim Quest 3: Amarna online:

preview Space Witches book 1

space witches book 2

Leena Maria's author blog

Tutankhamon's Golden Mask Coloring Page