EGYPTIAN AFTERLIFE

facts

To an ancient Egyptian afterlife was a positive thing. Death itself was not the end – it was considered to be only a short interval between physical life and entering the afterlife, the Duat. During this interval the proper mummification was performed, and you rested, waiting for revivication. The embalmers did their best, and even repaired damages to your body – if you were missing a limb or a body part, an artificial one could be put on its place. Even a toe prosthesis and false teeth have been found. It was considered important that you entered the Egyptian afterlife, Iaru, or the Field of Reeds, with a complete body.

4th dynasty, tomb of Meresankh III, Giza (G 7530-40)

Mummification was considered to be necessary for entering the Egyptian afterlife – the mummy was the home for the ka and ba – or aspects of the soul of the deceased – without which the deceased would not be guaranteed an afterlife. Still, it was well known that tombs were looted and mummies destroyed in search of valuable amulets and jewellery, and so a statue of the deceased could also function as the home for the ka and ba.

And in case the statues were destroyed also, keeping the name of the deceased alive guaranteed the deceased’s continued existence in the afterlife, and so it was painted on the tomb walls.

If your name was completely erased, however, either by accident or deliberately, you would die again in the afterlife. So you could say that even if the mummies were important to the ancient Egyptians, all that was really necessary for you to survive in the Egyptian afterlife was the memory of your name. (Which gave hope to the very poor who had no means to pay for the mummification.)

Once the mummification was finished, and the deceased was carefully wrapped in linen, it was time to revive the senses of the deceased one so they could enter the afterlife. For this the Opening of the Mouth –ceremony was performed, usually by special priests. The idea of the ceremony was to bring back the senses of seeing, hearing, touch – basically all the senses of a living person. To get back the ability to speak was especially important, as the deceased would need it at the Weighing of the Heart –ceremony, where s/he needed to speak to the gods and assure them that his/her life had been free of sin.

The eldest son of the family was considered to be responsible for the funeral arrangements of the parents. And actually it was seen as a prerequsite for inheriting your parents. Your inheritance was not questioned if it was known you had performed the last rites to your parents.

After the ceremony of Opening the Mouth it was believed that the ba, or inner self of the deceased, moved freely about. It could ascend to the sky and join Ra in his solar barque. It could also go to the world of the living. At night ba rejoined the mummified corpse at the tomb. The ba is shown in ancient Egyptian art often as a bird with a human head.

Sarcophagus lid of Djehapimu, royal audit officer. 746-332 BC. Room 0.12: Journey to the underworld - Egyptian courtyard, Neues Museum. BerlinÄM 49. Photo copyright Heidi Kontkanen.

After the Opening of the Mouth the family and friends of the deceased had a last feast with the mummy present, and after this the deceased was taken to his/her tomb. It was now believed that the perilous journey to the Egyptian afterlife began. The dead person had to pass through a series of gates, earch guarded by a demon. The way to pass them was to name the demons, and recite proper spells. This was helped by placing the Book of the Dead in the tomb – all the necessary spells were written there (of course the very poor could not afford this, as the book could cost a year’s worth of income)

Book of the Dead of NeferiniPtolemaic, 2nd-1st century BC Room 0.12: Journey to the underworld - Egyptian courtyard Neues Museum, Berlin. Photo copyright Heidi Kontkanen

Once you made your way past the demons you entered the Hall of the Two Truths. Here you faced 42 gods you had to convince you had lived a good life. At first the deceased used to say they had done good deeds, but later in history this turned into “negative confession” which meant you told the gods what you had NOT done. “I have not done (and then you would state an act that was considered to be a sin)”. Like “I have not stolen”.

Once this protestation of innocence was over, your heart was weighed on a scale against the feather of Maat – Maat being the proper way of things, or justice if you will. (Maat was a goddess who was personified as a sitting woman with a feather on her head). If your heart was heavy with evil deeds it weighed more than the feather. If this happened, a monster called Ammit – the Devourer of Souls - ate your heart, and you were undone as if you never existed. No afterlife for you. (There has not been found any reference of someone being condemned to this fate, so it seems the Egyptians trusted they would get in to the blessed afterlife)

The god of wisdom, Thoth, wrote down the verdict of the weighing of the heart. If (when) you were allowed to proceed, you were taken to the god of the Egyptian afterlife, Osiris. You could then join your loved ones and live eternally with them in Duat.

Fragment of a tomb painting with food offerings on the table. 18th dynasty, provenance not known, probably from Thebes.05.390.

supporting the egyptian afterlife from the world of the living

Still all was not done yet. The Egyptians believed that you needed sustenance in the afterlife as well, and this was provided through burial goods and tomb paintings. Scenes of feasts, tables laden with food were important. They were believed to magically turn into real food in the afterlife.

Also what is called the “offering formula”, hotep di nesu, was written on the walls of the tomb, and also outside the tomb for passers-by to read.

Reading it aloud would give the deceased bread, beer, fowl, meat, linen and all things good and pure in the afterlife.

Still, as only about 1% of the population was literate, perhaps the paintings of food and actual food offerings to the deceased were considered to be a more reliable way to provide for the afterlife. You couldn’t really expect a literate person to pass your tomb by very often. The well-to-do could hire a mortuary priest who would take care of reading the offering formula every now and again, as well as make food offerings. Pharaohs had veritable cults, where several generations took care of the offerings to the deceased king.

Stela of Maaty and Dedwi, probably from Naga el-Deir / 39.1 Brooklyn Museum. The hetep-di-nesu offering formula begins at the upper righthand corner, and is read towards left.

And a better view of how the offering formula was written (here read from left to right). Detail from the Sarcophagus of the Hathor Priestess Henhenet. The lid of this sarcophagus was severely destroyed. The lid presently in place belonged originally to the sarcophagus of another royal lady named Kawit.

11th dynasty, from Deir el-Bahri.07.230.1a, b. Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the tomb paintings the deceased was shown in a favorable light – as young and healthy and prosperous as possible. Dressing in your finest was important. Also as life was thought to continue the same as in physical life, hunting, building, fishing and all sorts of everyday activities were shown in the paintings. These paintings had deeper symbolical meanings too: hunting and fowling represented controlling the chaos of the universe – animals were seen to represent this chaos. Before New Kingdom the paintings represented the physical life of the deceased, and during New Kingdom the paintings began to show the ideal life in the Duat with gods.

Nebamun is shown hunting birds, in a small boat with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter, in the marshes of the Nile.EA 3797718th Dynasty, Thebes. British Museum. Photo copyright Heidi Kontkanen.

Still, it was not always believed that everyone had an afterlife. In the early Old Kingdom it was believed only the king had a ba and could ascend to the heavens and travel with the sun god Ra in his barque. The subsidiary burials of the early kings may testify to the belief that if you were buried with your king, you would have an afterlife serving him. The pharaoh’s afterlife was associated with the norhern, imperishable stars at first (these stars were around the Pole star of the time, which was Thuban in the constellation of Draco, and these stars did not set during the night). Later, when worship of the sun became more important, the pharaoh was identified with the rising sun. The orientation of the temples changed too as a result towards east.

Later on the chance of an afterlife spread to lower classes as well. But still, all along, it was believed your social status remained the same even in the afterlife. Work was required but you could skip this by having shabtis in your tomb. Many tombs had model boats in them, which reflected the idea that there was a river in the afterlife as well, and boats were necessary for transport.

In the course of history the deceased were believed to become stars, to live in the Fields of Iaru, to become united with the god Osiris, or travel in the barque of the sun god Ra – or all of these.

Dying abroad was a horror to an Egyptian – you could not expect an Egyptian afterlife if you were buried abroad, and so there are stories of sons fetching the bodies of their deceased fathers so they could be buried in Kemet.

Stela of Akhenaten and Nefertiti in front of an offering table. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, about 1345 BC. ÄM 17813

The Amarna period also threatened the idea of Egyptian afterlife. During this brief period it was stated that the dead slept in their tombs at night, and did not go to heaven. Instead they flocked to the offering tables that were placed in the great temples of the Aten in the city of Aketaten. Archaeological finds in the city prove that people did not abandon their own beliefs and worshiped old gods in the privacy of their own homes. No doubt they kept their old afterllife beliefs as well.

People very much believed their dead family members were alive in the Egyptian afterlife (or Duat), and had an interest in the lives of the ones still alive on earth. Sometimes their attentions were not considered friendly. Letters were written to the afterlife, often in bowls that were left at the tomb. The help of the deceased was asked, and if something had gone wrong in the lives of those left behind, explanations were demanded and the deceased was assured the living had done nothing to hurt them.

The beliefs of the ancients Egyptians in an afterlife, and the thousands of years their beliefs developed have supplied us with an endlessly fascinating field of research.

egyptian afterlife quiz

1. Which was more important for existence in the afterlife?

2. The ritual to make the deceased able to move and act in the afterlife was called

3. What was the written help to pass the demons guarding the afterlife gates called?

4. Did the Egyptians always believed that everyone could enter the afterlife?

Back to Homepage from Egyptian Afterlife Facts

Back to Mummies from Egyptian Afterlife Facts

all about mummies and tombs

I wish to thank Heidi Kontkanen for her kind permission to use her wonderful photographs as illustration to this article about Egyptian afterlife.

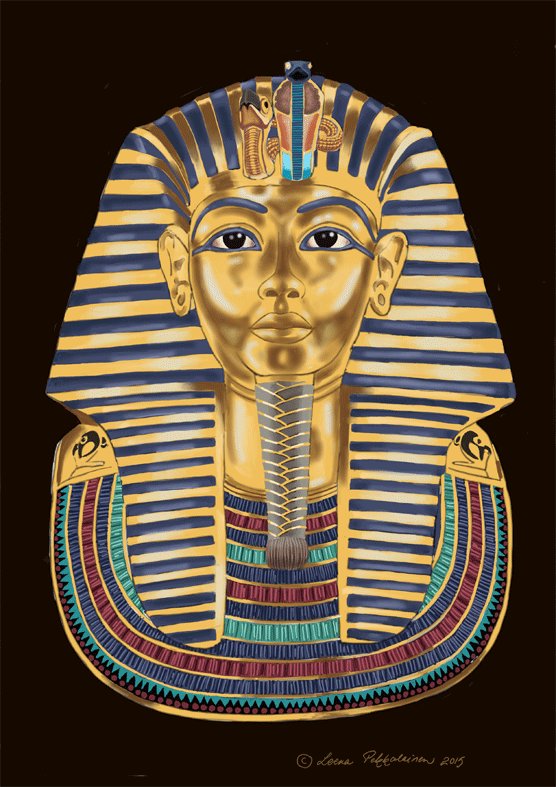

Tutankhamun: In My Own Hieroglyphs

|

Tutankhamun tells about his life - and death. The book that was chosen to travel the world with Tutankhamun's treasures world tour of 10 cities from 2018 onwards. |

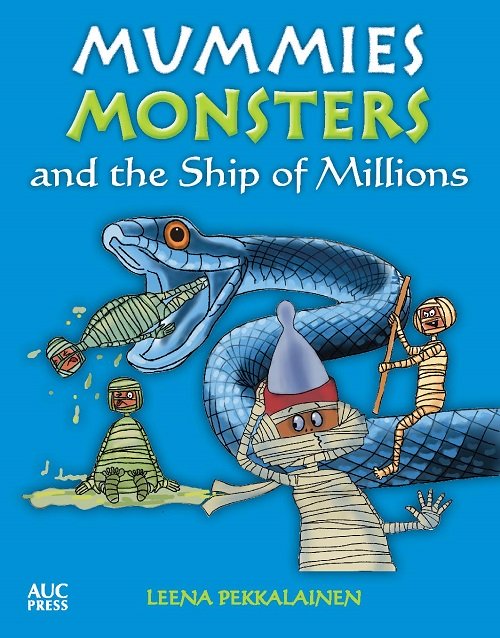

Mummies, Monsters and the Ship of Millions

Mr Mummific's hilarious journey through the 12 caverns of Duat to reach the Field of Reeds.

nephilim quest

Story of the search for one of the oldest legends of humankind, intertwining modern times and ancient Egypt.

preview Nephlim Quest 1: Shaowhunter online.

preview Nephlim Quest 2: MOON DAUGHTER online.

preview Nephilim Quest 3: Amarna online:

preview Space Witches book 1

space witches book 2

Leena Maria's author blog

Tutankhamon's Golden Mask Coloring Page